Today in Santa Monica, there is near-constant talk about the jobs-housing imbalance. The problem, simply put, is that because of decades of minimal growth policies, the city doesn’t have enough apartments, condos, or single-family homes to accommodate the vast majority of people who work here. Santa Monica’s daytime population swells by tens of thousands of people who can’t find places to live in the city. Everyday, they commute to work in our restaurants, hotels, hospitals, office buildings, and stores.

This isn’t a new problem, though. Santa Monica’s role as a major regional job center has ebbed and flowed throughout the years.

In December, the City Council established Santa Monica’s newest historic district, a swath courtyard apartments that line San Vicente Boulevard between Ocean Avenue and Seventh Street. This now-historic stretch of land stands as a testament to an earlier time in Santa Monica’s history when jobs were on the rise and the need for more housing to accommodate a growing work force was very real.

The city’s historic district report [PDF], prepared by Architectural Resources Group, Inc., explains the economic drivers that turned the blocks from a patch of single-family homes and commercial buildings into a collection of now-historic courtyard apartments.

In the 1920s, the stretch of San Vicente between Ocean Avenue and 7th Street had already begun to densify as single-family homes and commercial buildings were redeveloped into apartments, according to the report.

“In 1924, the five‐story Shoreham apartment hotel opened at Ocean Avenue and San Vicente Boulevard. The Shoreham offered maximum ‘home privacy and comfort’ with the ‘advantages of a luxuriously operated apartment hotel.’ Though on the grander scale of multi‐family apartment housing, the Shoreham established precedent for the construction of more modest apartment houses in the proposed historic district,” the report reads, citing a 1924 Shoreham advertisement in the Los Angeles Times.

“Four‐flats, duplexes, bungalow courts, and courtyard apartments began filling the empty lots between single‐family residences. By 1937, the stretch of San Vicente Boulevard between 1st Court, Ocean Avenue, and 7th Street was zoned R3 for multi‐family residential development, a zoning use largely non‐existent in the city’s neighborhoods north of Montana,” the report reads.

As the country recovered from the Depression and World War II loomed, more and more jobs came to Santa Monica, then home to one of the region’s biggest airplane manufacturing companies, Douglas Aircraft. There was a corresponding rise in the demand to live in the city. After the war, Santa Monica’s role in aerospace and other industries continued to drive a need for more housing.

“As with much of Southern California and Los Angeles County, Santa Monica’s population skyrocketed during and after World War II. The Douglas Aircraft manufacturing plant in Santa Monica employed thousands of local residents from the 1940s into the postwar years. Following the war, the RAND Corporation provided employment for hundreds of Santa Monica residents in the fields of mathematics, aerodynamics, engineering, physics, chemistry, economics, and psychology. As housing demands quickly exceeded supply, courtyard apartment complexes replaced smaller multi‐family dwellings and the remaining single‐family residences along San Vicente Boulevard,” according to the report.

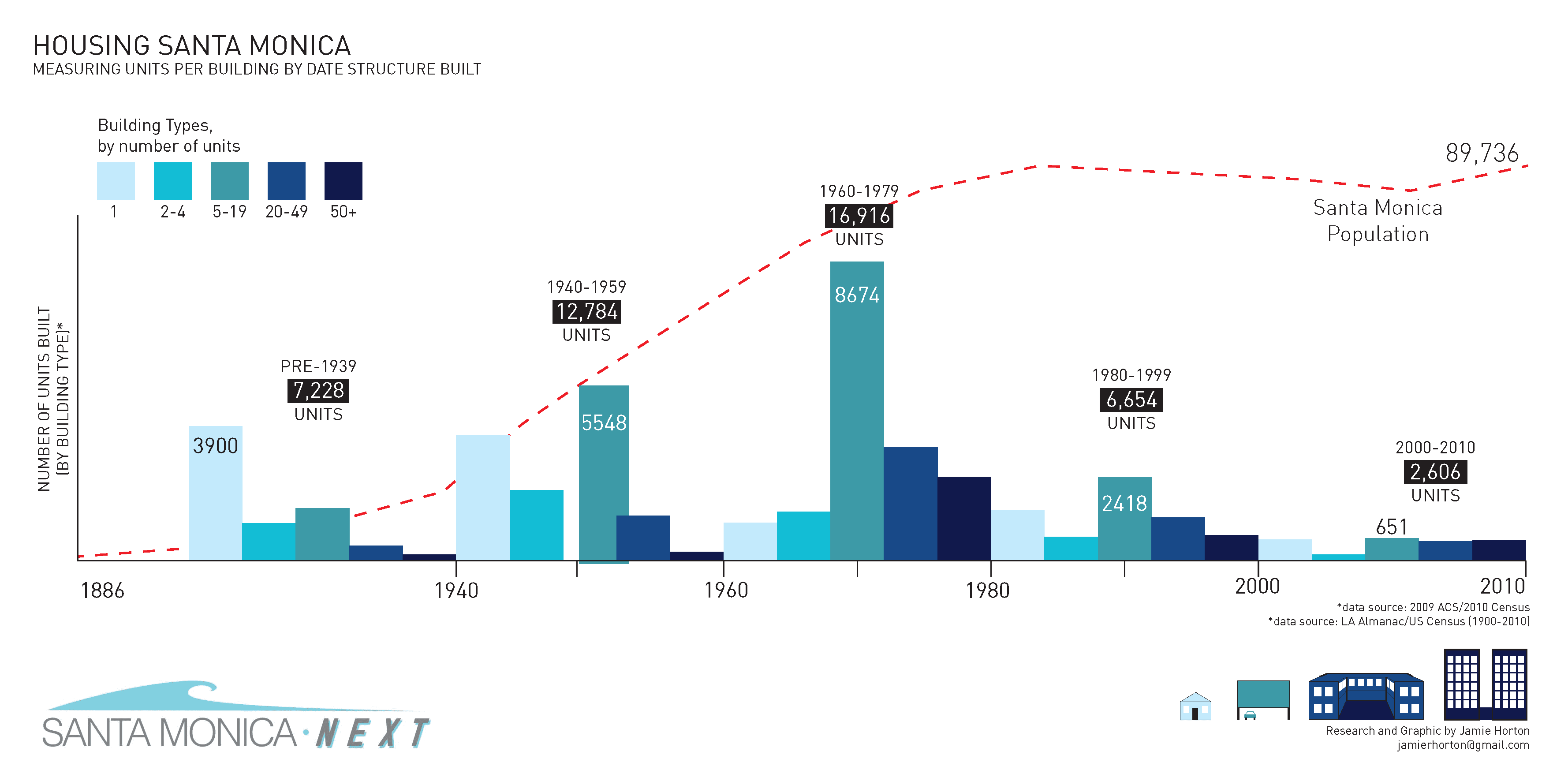

Santa Monica had been growing since its founding in 1875. According to the U.S. Census, in 1910, Santa Monica was home to 7,847. That number nearly doubled to 15,252 in 1920. In 1930, the population was up to 37,146, then shot up again in 1940 to 53,500 and in 1950 to 71,595.

The majority of the courtyard apartments in the new historic district were developed to replace single-family homes and commercial buildings during the growth spurts of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. It was in the same post-war era that Santa Monica’s Wilmont neighborhood — the area between Wilshire Boulevard and Montana Avenue — saw a similar pattern of densification as single-family homes were redeveloped for apartment buildings and condos as more people moved to Santa Monica.

As the aerospace industry left Santa Monica and took many industrial jobs with it, the city turned to commercial office space growth. Today, Santa Monica is again a thriving jobs center. Internet start-ups, a thriving hospitality industry, Santa Monica College, and other major industries employ thousands of people.

However, in constrast to previous eras, housing growth has slowed to a trickle.

In more than 30 years, Santa Monica has only built enough housing to allow for about a 4,100 net increase in its population. What will that mean for conservationists in 2080 looking to find historic housing trends from our era? Will we continue to regard dynamic housing growth as something exclusively from a bygone era?