It’s no secret that Santa Monica is one of the most expensive places to live in California, a reality that anyone who has tried to move to the city or even within it knows all too well.

While Santa Monica is a particularly extreme example, the city isn’t alone. Rents in Los Angeles County are growing faster than most other places in the country, forcing lower- and middle-income people to find places to live farther and farther away from their jobs and even out of state. But what’s driving these insane rents? And how can we fix this?

Well, a new report from California’s Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO), a nonpartisan advisory office that provides lawmakers with policy and budget analyses, offers an answer — and a solution — to this growing problem that is disproportionately burdening working Californians.

“The state is facing a growing housing affordability crisis that is hurting disadvantaged and working people and must be addressed by, among other strategies, a significant increase in the production of new housing,” said State Assemblymember Richard Bloom, who is a Santa Monica resident and formerly served on the City Council. His district — Assembly District 50 — includes neighborhoods with some of the highest housing costs in the state, including Santa Monica, Beverly Hills, Brentwood, and Malibu.

“The LAO report is their second in the last 12 months on the topic and underscores the importance of this issue,” he said, referring to a report issued last March by the LAO on the causes and consequences of California’s housing shortage.

“The Legislature is poised to address this issue in the State budget and with policy proposals. As a representative of a district where the crisis is acute and as a matter of concern for all Californians, I intend to be very active on both fronts,” he said.

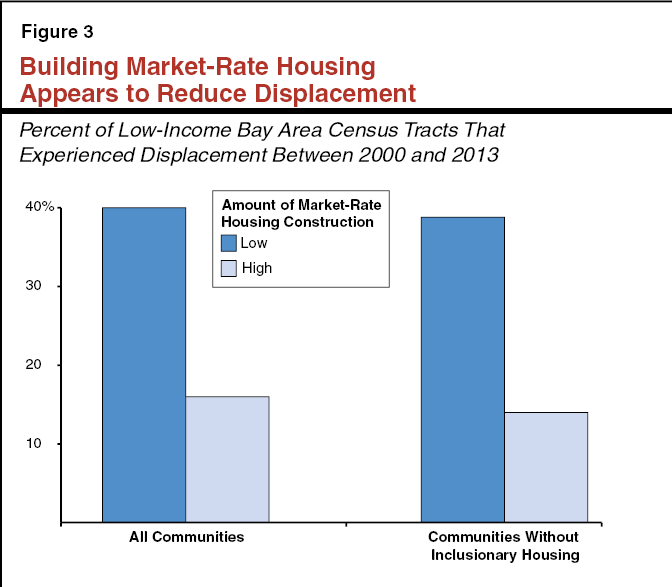

In short, the most recent LAO report says that if cities want to prevent lower- and middle-income households from being displaced, they need to allow much more housing to be built. According to the report, even new apartments, which tend to rent at high price points, benefit lower- and middle-income renters because more luxury apartments, as long as they don’t replace existing housing, mean less competition for homes in older buildings.

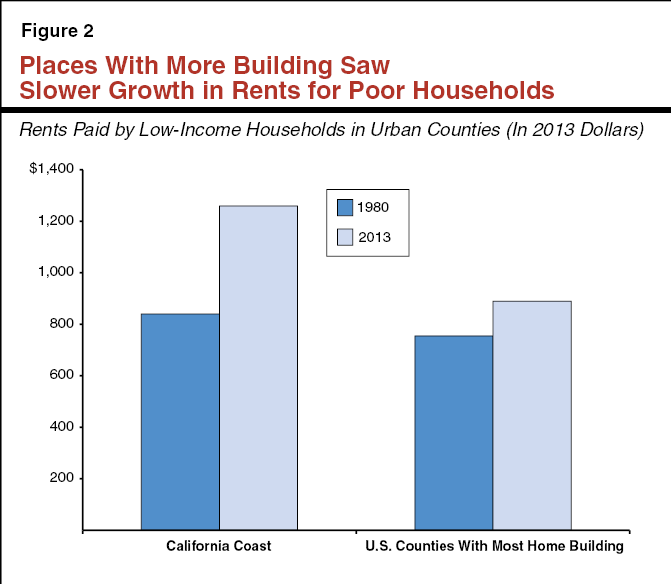

In fact, the report shows that in parts of the state that have seen higher rates of housing construction, the rents in older apartments have gone up much more slowly than they have in cities like Santa Monica, where housing growth has been relatively slow.

“Impartial analyses repeatedly show that building more market rate housing helps fight the forces that drive housing prices higher,” said Santa Monica City Councilmember Gleam Davis.

“If we are serious about keeping housing affordable and reducing the threat of displacement, we need to build more market rate housing,” she said.

City Councilmember Terry O’Day agreed with Davis’ statements.

“The study shows the link between market rate housing and affordability. Any housing built alleviates pressures on the lowest-income renters,” he said. “It should be a clarion call to build transit-oriented housing development.”

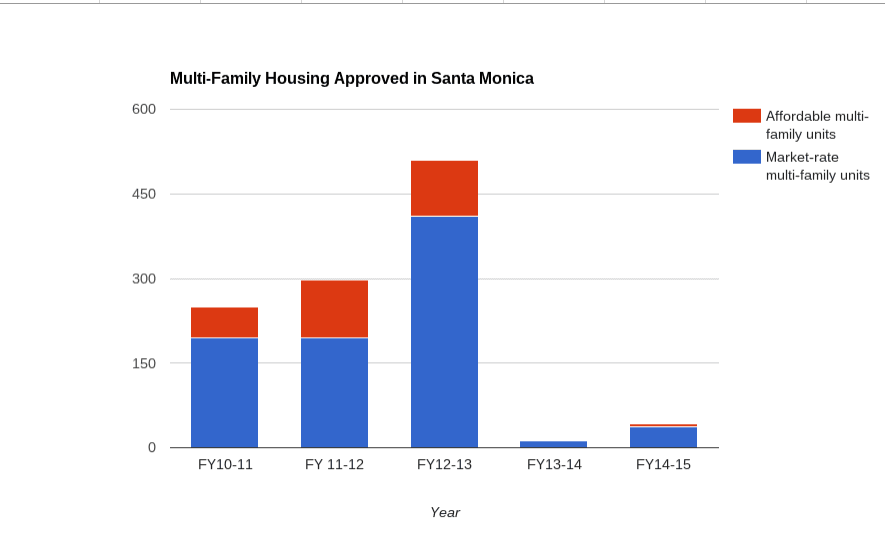

Santa Monica has a strict inclusionary zoning law that requires 30 percent of all new housing built in the city to be rented to lower- and middle-income households. Programs like this, while necessary, the LAO report says, are not sufficient to help the growing number of people in California — and especially in coastal cities — who are paying 50 percent or more of their paychecks to cover housing costs.

Santa Monica City Councilmember Kevin McKeown is skeptical of the new report, however.

“We always have to be careful in applying general conclusions about California, even specifically coastal California, to Santa Monica,” he said. “Much of our Santa Monica resident displacement comes through Ellising for gentrification, and we are such a desirable place to live that new market rate apartments are priced far out of reach of our low-income households the LAO report discusses.”

The LAO report actually notes that new market-rate housing benefits low- and moderate-income households because it gives higher-income people an alternative to competing with lower-wage earners for older housing stock.

Also, the report notes that what is “luxury” housing today, over time, becomes more affordable, especially to middle-income earners, but only if new housing continues to be built.

“Considerable evidence suggests that construction of market-rate housing reduces housing costs for low-income households and, consequently, helps to mitigate displacement in many cases,” the report reads.

McKeown notes the worrying trend of tenants being evicted from rent-controlled units by owners, which is allowed under the Ellis Act, enacted as state law in 1986, if the owner is going out of the rental business. Santa Monica has seen an uptick in Ellis activity, but that is likely due to its traditionally minimal-growth policies.

In areas where it is harder to build, landowners are more likely to spend money to refurbish old buildings to rent them at higher price points or to simply take those buildings off the rental market. San Francisco is an extreme example of what can happen when minimal growth policies collide with a booming high-quality job market.

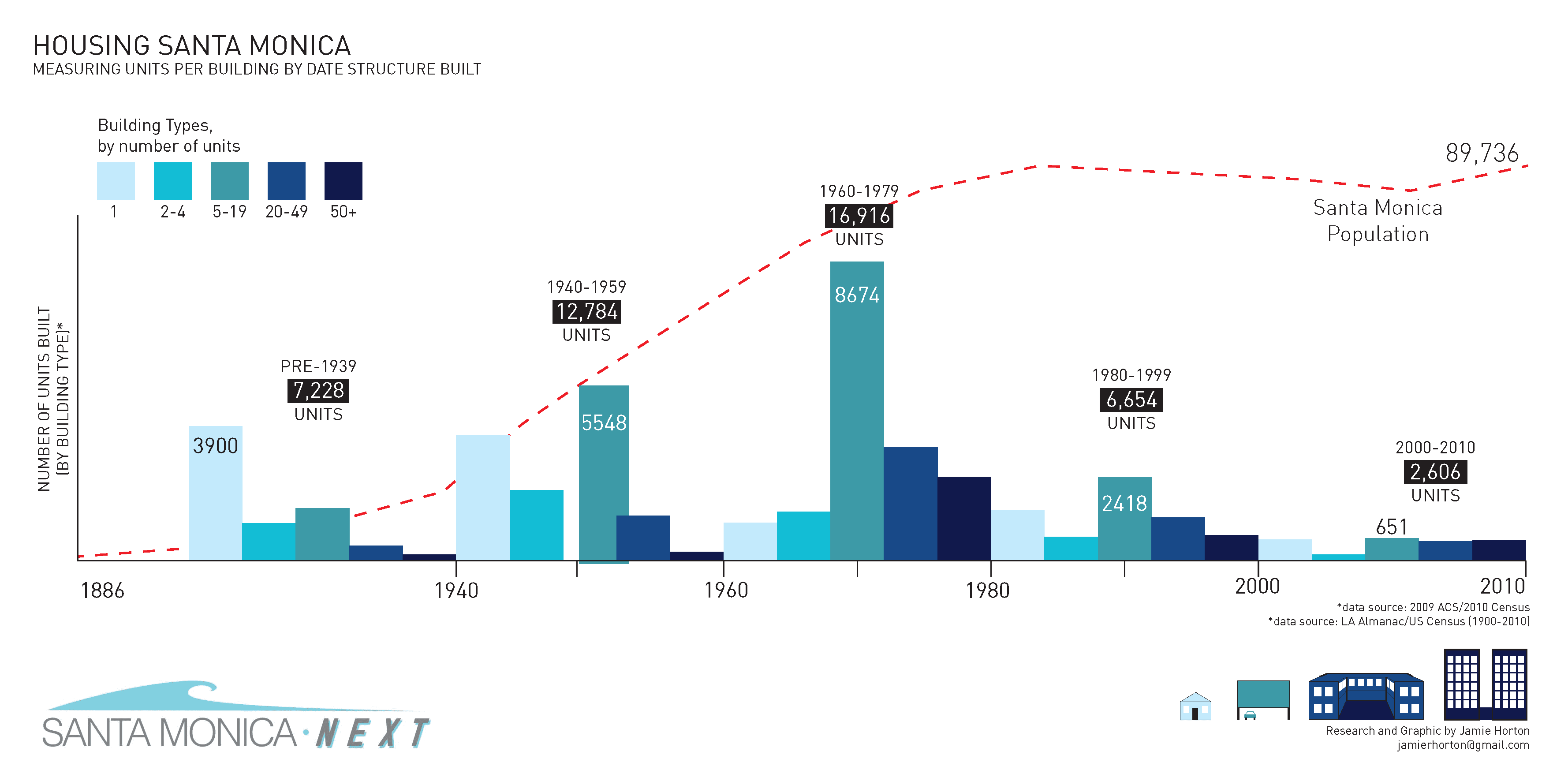

“Nonetheless, by focusing new housing construction where existing neighborhoods and neighbors won’t be displaced, we’ve begun to reverse a stagnation in new housing production in Santa Monica,” McKeown said. Since 1980, Santa Monica’s net population has only increased by about 4,100. Most of that modest growth happened in the city’s downtown core. This is especially important to note considering the city will release its revised plan for the future of Santa Monica’s downtown this Friday.

“We need to house our workers and our young people, because that’s the right thing to do. I wouldn’t want to guarantee, though, as the LAO report seems to generalize for California as a whole, that our Santa Monica housing efforts will soon result in lower rents in Santa Monica,” he said.

The LAO report prescription is one that requires regional — and statewide — coordination. Los Angeles County — which includes 88 different cities — has, since the 1980s, built about one million new units less than would have been needed to keep pace with demand and therefore slow down the astronomical rent hikes we are seeing today, according to the LAO report released last March.

Housing growth in Santa Monica is necessary, but not sufficient, to stem the problem of artificially high rents. Still, the problem is particularly dire on the westside, including Venice and Santa Monica, the area now known as Silicon Beach, where the last 30 years have seen plenty of new, high-quality jobs sprout up but relatively little new housing. People want to live where the good jobs are, but artificial zoning restrictions are making that harder and harder each year.