[pullquote align=left]

Residocracy wants to reduce traffic—the time price of accessing Santa Monica—by limiting the number of people who live here. That’s like trying to reduce the cost of the box seats behind home plate by reducing the number of people who like football.

[/pullquote]The downside of paradise is the traffic. And Santa Monica is a natural paradise. We’ve got wonderful weather, even relative to the rest of LA; we’re close to the beach and the mountains; we have a vibrant, walkable downtown; our own hospitals, college, and top-notch public radio station.

What’s not to like? The traffic, naturally. And it is natural.

But natural or not, traffic in Santa Monica gives a lot of people headaches. One newly minted set of grandparents wanted to go see their brand new granddaughter, born in the Valley on a Friday afternoon. No dice. After an hour and a half, they couldn’t make it as far as the 405 and had to turn around. In the life of a child, waiting an extra day is no big deal. But for those grandparents, it was a crushing eternity. A beautiful moment was ripped away from this couple, and traffic was the villain.

The recent Santa Monica WellBeing Index identified traffic as the top concern of residents of Santa Monica. Can anything be done?

Residocracy thinks so. Their plan is to cut traffic by limiting housing growth in Santa Monica through a ballot initiative — called the Land Use Voter Empowerment or LUVE initiative — for which they are currently gathering signatures to put on the November ballot. The LUVE initiative would require virtually all new construction over 32 feet tall be approved by the voters. Since the vast majority of new building in Santa Monica is residential, it would essential cause new housing growth to grind to a halt.

So a natural question is, is housing growth in Santa Monica contributing to traffic? Because if not, then there is no chance that reducing that growth will reduce traffic.

The first thing to understand is that Santa Monica is not just by the beach, it’s basically an Island. Barriers around Santa Monica include the ocean on the west, the Santa Monica Mountains to the north, the 405 to the east, and the airport and Penn Mar golf course to the south. There are, in fact, only seven roads through from Santa Monica to the east and five going south. You can go north on about 3 roads, but that just gets you to the Island of Pacific Palisades.

Once you’re on the Island of Santa Monica, traffic really isn’t so bad. There may be the occasional annoyance on 4th Street, but the real headaches are going east and south between 3 p.m. and 7 p.m. on weekdays. And that fact alone is our first clue that Residocracy is clueless.

Who is leaving town in the afternoon rush hour? A crush of new Santa Monica residents, going out to party in Westwood? I don’t think so. It’s all those people who work in and visit Santa Monica.

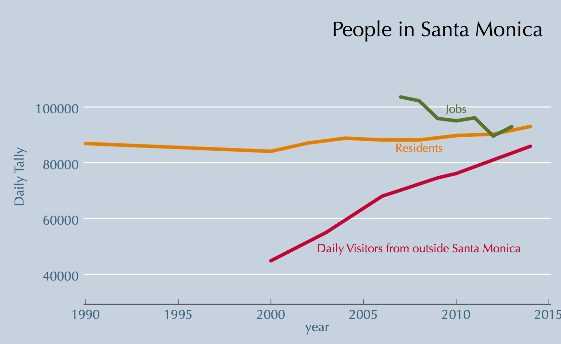

To see how their relative numbers have changed over time, I downloaded the 2015 Profile of Santa Monica published by the Southern California Association of Governments [SCAG]. I also scoured the web for old numbers of visitors from the Santa Monica Visitors Bureau.

Here’s what I come up with:

When Residocracy says they’re against overdevelopment, now it’s pretty clear what they’re against. It’s all the stuff that makes Santa Monica great: Santa Monica Place, the Third Street Promenade, the Beach, the Pier, Montana Avenue, Main Street, the parks, and so on. Residocracy wants a bedroom community: a nice, quiet place that no one visits. We could have that. We could turn our city into Beverly Hills, but we’d lose Santa Monica.

The thing is that traffic is a price. It’s the cost of accessing wonderful amenities like the beach, the Third Street Promenade, our many parks, or great jobs. If those things are worth an hour of sitting in traffic for at the end of the day, then the price will be an hour’s worth of traffic delay.

At a Dodger’s game, we’d all like to sit right behind home plate in about the 4th row back. The trouble is, there aren’t that many seats there, so the price of those seats is high.

There aren’t that many ways out of Santa Monica at the end of the day, so the price of those roads—in terms of the time it takes to go four miles—is high. Residocracy wants to reduce traffic—the time price of accessing Santa Monica—by limiting the number of people who live here. That’s like trying to reduce the cost of the box seats behind home plate by reducing the number of people who like football.

Living in paradise is great. Traffic is just the price we pay for it.

Of course there are things that can be done. A report by the Rand Corporation outlines several of them. Subsidize the bus system. Create—and enforce—bus-only lanes on Wilshire. Charge for parking downtown and plough the money back into sidewalk, bike, and bus system improvements.

All these things won’t make much difference for the average speed of cars through town. But they make a huge difference to the average speed of people through town. So depending on whether you care about cars or people, they can make a lot of sense.

Even more radical strategies are possible as well. One community cut the local speed limit to 18 miles per hour and saw the quantity of traffic decrease.

The one thing that won’t help? Limiting housing development. The Residocrat fantasy world doesn’t exist, and the LUVE initiative is a losing proposition. It won’t stop traffic, just take a small bite out of paradise.