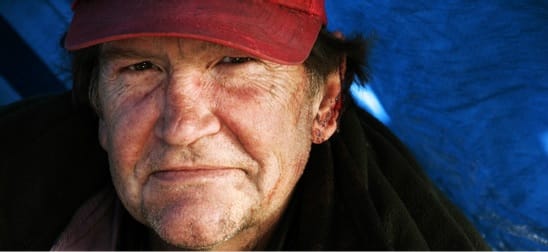

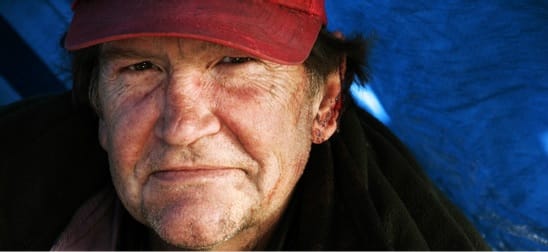

The city of Santa Monica is looking for volunteers to help with its annual homelessness count, which helps the city keep tabs on and take steps to address the growing problem of people without shelter.

Those interested in helping with the count, which takes place overnight on Wednesday, January 24, can register here.

Last year’s count revealed that the number of people bedding down on Santa Monica’s sidewalks, in shelters, or in cars was the highest it has been since the city started performing the count annually in 2009, when participants counted 912 people. In 2017, volunteers counted a total of 921 people.

The increase in the number of people struggling with homelessness in Santa Monica mirrored a troubling trend seen throughout Southern California.

“The significant increase since last year demonstrates that the [c]ity is directly impacted by the regional homelessness crisis,” city officials said in the press release that accompanied the announcement of the 2017 homelessness results in May. “Last year [2016], the regional count reported in excess of 46,000 people experiencing homelessness and 76 [percent] living on the street.”

While many factors contribute to the recent rise in homelessness, one major factor is that L.A. County’s housing shortage, which disproportionately impacts lower-income residents as it drives up rents, has come to a rolling boil.

In May, 2017, Human Services Administrator Margaret Willis told Next that the L.A. Metro area has had a rental vacancy rate of three percent, which indicates a significant shortage of housing relative to demand.

“This scarcity means that homeless [people] and very low-income households are competing with middle-income households for the same units,” Willis wrote in an email responding to inquiries from Next about the results.

“This means people either a) are forced to take an apartment that may be more than they can comfortably afford, making them vulnerable to homelessness…, or b) they double and triple up, again making their housing unstable and unhealthy, or c) they stay homeless,” she said. She referenced the city’s Wellbeing Index, which reported that about 20 percent of Santa Monica residents worry about paying rent or a mortgage.

Last year, the legislature pushed a hefty package of bills aimed at funding affordable housing and making it easier to create new housing in urban areas, but State Assemblymember Richard Bloom (D-Santa Monica), one of the Sacramento’s most vocal housing champions, noted that the legislative package, historical though it was, is only a start.

State Senator Scott Wiener has already introduced an aggressive housing bill that is likely to be controversial.

“Subject to some limitations, the measure would eliminate restrictions on the number of houses allowed to be built within a half-mile of train, light-rail, major bus routes and other transit stations, and block cities from imposing parking requirements,” wrote L.A. Times reporter Liam Dillon about the bill.

As Bloom has noted in the past, while housing growth is necessary as a long-term solution to the housing affordability problem in California, immediate relief is needed for the most vulnerable among us.

The future of federally-funded programs like the Housing Choice Voucher Program, more commonly known as Section 8, remain unclear under the current administration. In Los Angeles alone, 188,000 people applied for 20,000 spots in the housing voucher waiting line.

Last year, Bloom pushed AB 1505, which officially clarified that cities could pass inclusionary housing laws, which allows municipalities to require developers build affordable housing as part of market-rate projects.

Still, much of the housing shortage problem comes from local opposition to new housing, including affordable housing.

Santa Monica voters recently approved Measures GS and GSH in order to help fund affordable housing, but at the same time, locals continue to fight most growth.

In 2016, Santa Monica approved 380 new units. The vast majority of them, 318, were part of one project that took several years to negotiate and will likely take several more years before they come online. The project, 500 Broadway, included 249 market-rate units and 64 deed-restricted affordable units located a couple of blocks away, a result of Santa Monica’s inclusionary housing rules that require developers to provide affordable housing when they build new, market-rate housing.

Since 2012, Santa Monica has lost out on at least 1,000 units, all proposed in projects that would have redeveloped outmoded commercial or industrial properties, as a direct result of local opposition.

And, last year the city council narrowly passed standards for the city’s Downtown that reduces the area’s capacity for housing growth.

Santa Monica has recently taken some more steps to help those in the city on the verge of becoming homeless by providing a basic income subsidy through the “Preserving Our Diversity” program, among other steps.

Of course, housing alone won’t be enough to solve homelessness. Many people struggling with homelessness also deal with chronic mental illness and require support services. Service providers say these must be paired with housing. An example is the Step Up on Colorado Kaufmann building, which put 32 homes for formerly homeless people in the service-rich area of Downtown Santa Monica.

The city of L.A. passed Measure H in November 2016, which will raise $1.2 billion for supportive housing projects, and L.A. County voted to approve Measure HHH, which will provide an influx of money for supportive services for people struggling with homelessness.

But for those who are not struggling with mental illness and simply living on the economic edge, Willis told Next in May, “affordable housing and livable-wage jobs are key to the success for these households, as they will need to be able to afford rent on their own after the assistance ends.”